Unless your band is The Supremes, The Ramones, or AC/DC and you’ve already hit on perfection, there’s no shame in adapting your art to suit the times, in evolving it to reflect your changing interests, knowledge, and personal development. Legacy artists have often found well-springs of creativity and challenge (not to mention commercial success) by incorporating contemporary sounds: Bob Dylan got to the peak of the hit parade by ‘going electric’ in 1965; Marc Bolan had loads of early 70s UK smashes by switching from airy-fairy folk to glam rock stompers; the Stones made it to number one (their last) in 1978 disco style; Billy Joel reframed his petulance as New Wave angst and topped the charts in 1980; Miles Davis’s and David Bowie’s whole modus operandi was based on their remarkable abilities as prescient musical changelings. And so on.

This is not to say that trend-hopping always pays off commercially: For every ‘Da Ya Think I’m Sexy’ smash, there’s a Further Adventures of Charles Westover by Del Shannon, a Flush the Fashion by Alice Cooper, and a Modernism: A New Decade by the Style Council dud. Still, these records, and others like them, have their defenders and have been subject to critical reappraisals.

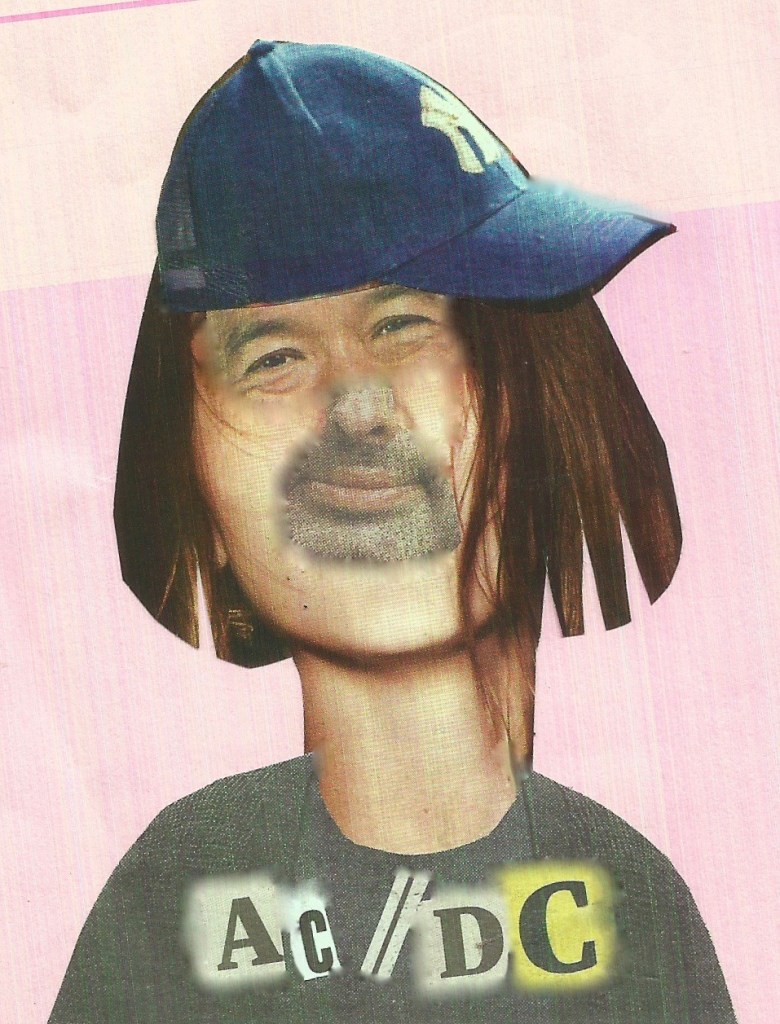

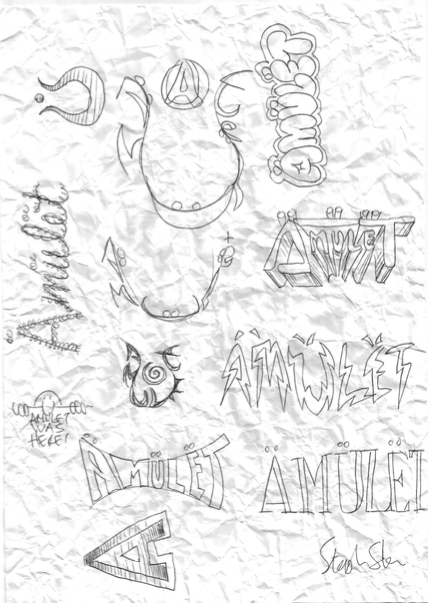

Perhaps the unluckiest, most prodigious practitioner of the serial bandwagon jump in musical history is Chicago’s own Ämülët. Or more specifically its founder member (and the lone musician to appear in each incarnation), Steven Merrilees. That Ämülët eventually settled on music that was broadly Americana in style is the reason they’re to be found within these pages.

Merrilees grew up a foster child who, by age eight, had already lived with four different families. Like so many of his generation (and the one just previous), Merrilees’s introduction to performing consisted of playing along with Beatles’ records on a tennis racket in front of his bedroom mirror. His first band, Taking It To The Streets, was formed in the 10th grade and consisted of 7 teenagers singing along to a Radio Shack C-60 cassette tape of the contemporary Doobie Brothers’ hit album. After their first rehearsal, Merrilees suggested the gang “jam on a riff” he’d been driving his latest carers crazy with for the previous six months. There was no room for such freethinking in Taking It To The Streets, and the band asked him to leave.

Within weeks, Stephens had formed his own group, The Slick Backs, and was covering all the songs on Sha Na Na’s 1969 début Rock & Roll Is Here To Stay. He had a hyperactive, twitchy way about him when singing and his energy levels, irritating in one-on-one situations, were a positive boon onstage.

After a visiting “uncle” hipped Merrilees to Slade and urged him write his own tunes, out went the 50s Rock & Roll and in came the spangles, meat & potatoes riffs, and fey suburban poetry, inspired by the likes of Gary Glitter, Mud, and Sweet. Merrilees was convinced that Glam Rock was the way to fame and fortune.

All he needed now was co-conspirators. Shortly after, almost as if the gods had decreed it, Merrilees was introduced to the cross-dressing, multi-instrumentalist Mitchell “Michelle Strange” Strand at the Happy Cow food processing plant where they both had recently started part-time jobs, and Ämülët was born. It was not to be a “When John Met Paul at the Woolton Village Fête” event, but they weren’t to know this at the time and proceeded as if it were, discovering two more musicians at Happy Cow.

By the time this gang of meat packers formed Ämülët in 1978, its members were only recently out of high school and the band were able to spend all its free time rehearsing. Because of their dedication, they were offered quite a few support slots for national bands passing through the Windy City. On one such occasion, opening for The Romantics, they were spotted by Rick Gantz, A&R for Made-Up Music, and the band was on its way.

Their début 7″ “Lips & Earholes” (the original title, “Lips & Assholes”, was rejected for obvious reasons) jokily alluded to the band’s experience on the killing floor mopping up the bloody detritus and carting it off to the Happy Cow’s hot dog department. Unfortunately, Glam had ceased to be commercially or artistically viable at least five years previously; they had just missed the boat. The single, as with its parent Lp, Smell My Love (Made-Up Music, 1980), was so out of step with the times that even the archest of ironists couldn’t get behind them. That, coupled with the fact that few at the label really understood, or indeed particularly liked, the record, meant it stiffed and Ämülët were summarily dropped. One young intern tartly complained, “How am I supposed to do The Worm to this?”

The boys regrouped and did some soul searching. They knew that some sort of change in direction was in order, but which direction? Taking a late-night Showtime screening of Saturday Night Fever as a sign to ‘go Disco’, Merrilees urged Ämülët to follow that route. Despite some misgivings from the other members, Merrilees pressed on with his foray into pop-dance music, resulting in 1985’s Boogie Noogies (Casanegro Records & Filmworks). Alas, a minor country-wide backlash six years previously made the genre anathema to the record buying public and, as with the band’s previous phase, sales went nowhere in a hurry. Three years of gigging in white suits and middle partings were for naught.

Short-lived New Wave and Motown directions were signalled with the releases of The White Albumin [Smooth Brain, 1989]) and Souled Out (Engineville, 1994) respectively. Once again, timing was not on Ämülët’s side and both records fizzled due to being hopelessly out of fashion. Next, fully six years after Kurt Cobain was discovered lying dead in his Seattle home, Ämülët turned in their grunge album, Heavy Modal (Stoner Island, 2000), which was met with similar indifference and confusion.

By this time, Ämülët had run through seventeen different drummers, nine bass players, and three keyboardists, Mitchell Strand having long departed to start his own project managing a traveling Burlesque show called Vavavoom! Merrilees was beginning to believe his dreams of musical fame might never come true.

Now, it is a curious fact, but if you hang around long enough, you can, almost by default, become ‘legendary’. Also, styles that go all antwacky often come back into vogue via hipsters bent on provocation. Disco, New Wave, Psychedelia, and etc. have all had periodic renaissances following years of critical disregard. During these revivals, Ämülët’s relevant records would pique the interests of crate diggers, doing much to keep the group’s brand afloat. Because of this, and the fact the band was still remarkably beloved by local club owners, many of whom managed to mismanage them through their various phases, they were still landing decent support slots. They opened for The Jayhawks, Son Volt, Wilco, Cracker, among other Americana heavy-hitters, all in the span of two years in the late nineties. Soon, Merrilees showed up wearing a cowboy hat to their weekly rehearsals. At this point, the rest of the band just signed on without much of a fight.

With the 2008 release of the Country-themed Harvested (Ovaloid Records), the band, apparently creatively exhausted by its myriad volte-faces over three decades, manfully clambered onto its last caravan. At least C&W is a style into which one may gracefully grow old.

Mumbled in a gravely tone with the most convincing southern accent a suburban Chicagoan could muster, their lyrics still made no sense whatsoever. But slap on some basic acoustic guitars and fake steel guitar (opened tune electric through a Green Line-6 delay), add the best reverb that Pro Tools can buy and you had yourself a song. A couple of which actually got into a few films thanks to a few Hollywood film and television soundtrack friends who placed the tunes in early edits that the director just got used to.

Pitchfork, who had until this point completely ignored Ämülët, suddenly took interest when one of the songs appeared on Freeks & Geeks, noting enthusiastically that the “long-lived Chi-Town chameleon outfit’s latest tune was better than mediocre.” Their second release for Ovaloid, All The Gritty Forces (2010), upped the quality still further and the band began to talk up a 30-years-in-the-making overnight success.

Alas, it all came quickly tumbling down in what should have been a breakout appearance during SXSW at the Continental Club, where Merrilees, likely worn out from a heavy touring schedule, and most definitely drunk, began insulting nearly every band in his current genre from onstage.

“The Jayhawks are a bunch of old white guys,” he complained. “They don’t even like each other.” He rambled on. “Wilco? Gimme an f’in’ break! How many guys showed up to sign that record deal in the documentary? I’ll tell you how many: One! That ain’t a real band is it? Now, Drive By Truckers, that is a band, but how many albums can they make about the South being such a shithole?” The room, chock full of industry insiders and tastemaker went silent, there was no turning back from this. Steven Merrilees had not merely shot himself in the foot, he had blown both of his legs off.

The show effectively shut the door on Ämülët as going concern. Bookings completely dried up and record contracts were voided. A subsequent Post Rock recording made under another name, Pink Slime*, was sniffed out and rejected. An album of children’s songs Steven recorded for his grandkids, Merrilees We Roll Along, also remains unreleased.

It’s true that provincials are often a year or two behind the times and, on that score, Ämülët certainly started as they meant to go on, so that by the time the band had made each jump, the wagon had long left the depot. With each radical change in approach, Ämülët would alienate the few fans they’d managed to gather in the meantime and, for all practical purposes, have to start over from scratch; hence the five to ten year wait between releases. The thing is, every time they swapped their image they would proclaim, in total Stalinist capitulation to their new style, that, at last, “You’re seeing the real Ämülët!’

*Another allusion to Merrilees’s early days at Happy Cow.